If you read any book on screenwriting, you will find that the recommended method is always the same: Plot out the story. Use notecards. Filmmakers have to make sure every scene is mapped out because it’s way too expensive to change the story around after you have already shot the first half of the movie.

Not only that, but most movies have similar plot structures. My favorite method is the Blake Snyder method, an abbreviated version of which is as follows: The protagonist’s world changes at minute 12; after some debate, he decides to go on his quest at minute 25; a dramatic setback occurs at minute 55; he achieves his goal at minute 75 but now realizes he has even bigger problems than he did when he started; and finally, he makes a heroic decision at about minute 85 that sets the end of the movie in motion.

Despite the plotting and the formulaic structure of the Blake Snyder method or any other plot guide, many movies somehow seem to be fresh. Even though the plot points of Jaws and Jurassic Park are basically the same, they’re both fun to watch. And Pixar movies follow these plots exactly, and they still make people cry. (Of course, I’m a Cormac McCarthy fan, so they don’t make me cry!)

So what does this have to do with novels?

Have you ever noticed that a novel has either beautifully written sentences or an exciting plot, but very rarely does it have both? My theory is that there is just not enough time or energy spent on the plot. Instead, novelists feel they need to let the characters wander and be free spirits; otherwise, they seem to believe, the story will feel too calculated.

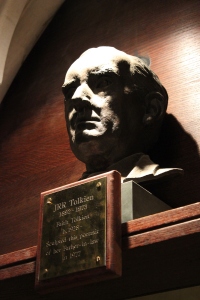

There is a great story about Flannery O’Connor, who said that she only discovered the surprise ending to “Good Country People” about 10 lines before she wrote it. J.R.R. Tolkien supposedly knew only as much about Strider as the Hobbits did when he first appears in the Fellowship of the Ring. Those examples are evidence of inspiration that occurred in the process of telling the story. Writers who discount plotting have likely experienced those exhilarating, lucid moments while writing and want to be led by that magic and only that magic.

But magic can happen in a plotting session, too. And, if that kind of inspiration happens while a writer is in the middle of writing a scene, the plot map can always be adjusted.

All this leads me to this question: if you can plot out a movie and still deliver an emotional impact in the final product, why is it that literary novelists think it’s heresy to plot out a novel? Today’s blog post (Sept. 20) on http://www.BlakeSnyder.com is by an author named Chris Kohout, who says he used the classic 15-point Blake Snyder Beat Sheet to map out his novel. I’m not saying it’s a great literary novel–I haven’t read it–but I’m guessing that Kohout also discovered the same thing that I have by trying to map out the first draft of my first novel, and that is that, just like a moviemaker, a novelist can save a lot of time by making a plot map.

Proof positive: Because of the work I did in plotting, and because I stuck with a schedule of writing for 60-90 minutes, Monday through Friday, I was able to complete my 85,000-word draft in five months.

In the early stages of the novel, I used a point-of-view character named Martin. I thought it would be interesting to write about a black man who saw racial implications in the actions of others all around him. But the more I wrote about him and then wrote about other characters, I realized that, although the issue of race is fascinating and deserves serious thought and writing, his character didn’t feel particularly alive to me. So, I chopped him out, losing 8,000 words or so from my draft. Maybe I’ll rediscover him someday in another story.

But if out of 85,000 words, I only made one significant 8,000-word wrong turn, I have to be satisfied that the process was efficient. Whether it was effective remains to be seen. Hopefully I’ll be able to write a celebratory blog post someday about how I got a tremendous book deal. In the meantime, at least I feel confident that when I come across the next novel-sized idea, I have a way to get started.